Kentucky Route Zero is a beautiful game. It's stunning in all aspects—visually, poetically, thematically—and it explores many important, often poignant, themes of loss, debt, grief, as well as curiosity, perseverance, and adaptation.

The game's official description reads as follows:

Kentucky Route Zero is a magical realist adventure game about a secret highway in the caves beneath Kentucky, and the mysterious folks who travel it.

At its crux, Kentucky Route Zero (KRZ) is about people. It's about people with stories (nonetheless fictional, or mostly fictional)—stories that provide human connection and emotion-based interaction, and that engage the listener/player. The game description does its job in beginning to encapsulate the game's many complex themes and overtones, and ends on a note which implores players to discover, learn, and explore.

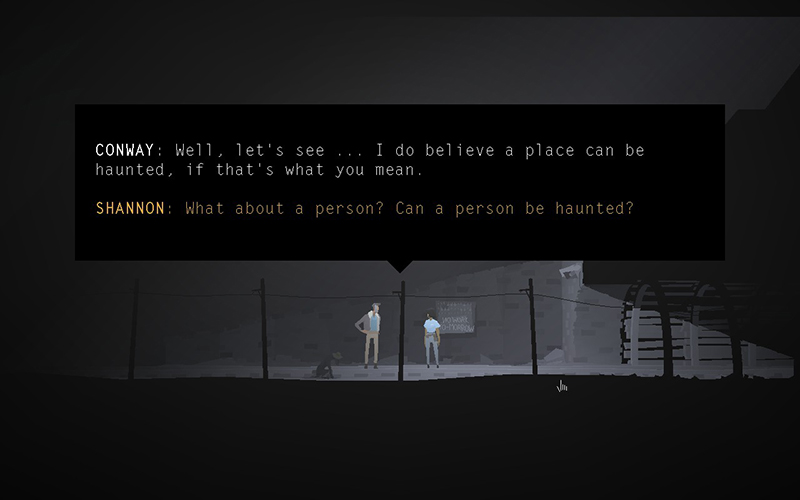

"It is important for me in thinking about working on a video game that it be about being alive right now," says developer Jake Elliott. Even with only three acts completed out of five total, the game and its story so far accomplish this in full. KRZ is not about prescribed dialogue or stories, but about the human connections and moments found in players' experiences with these stories. It is the sum of these individual moments that serves to create an experience that is authentic, haunting, and real.

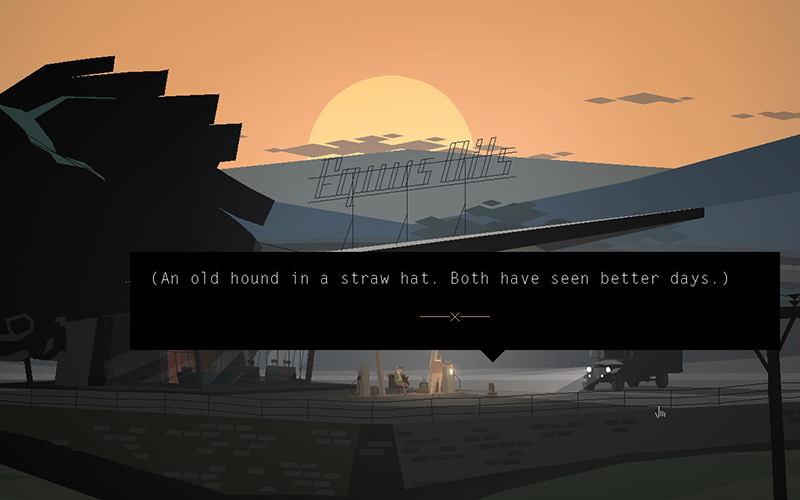

At the start of the game, as Conway and his dog step out of his truck, players are prompted with a symbol to look at or to inspect the dog, to learn more about it or its story. You click, and the dialogue box appears.

"An old hound in a straw hat. Both have seen better days."

You read, and you feel something—the seal of anonymity is broken, and you are granted a connection. This is the first description presented to players, and it's usually the piece of text I quote when giving an example of the game's writing and presentation style. It's beautiful, descriptive, succinct yet thorough, and nostalgic. It's reminiscent of better days, ones of better health but perhaps less wisdom. It gives the hat a history, and begins to reveal that of your four-legged companion as well. It hints toward the existence of experiences, unknown but nonetheless present in histories of both the animate and inanimate. Perhaps it's trying to be poetic, but that's okay here. There's a precise juxtaposition between the rhythm, prosody, and balance of the first sentence and the brevity of the second. "An old hound in a straw hat. Both have seen better days." The text does its job, setting the stage for the rest of the game and for the story to come.

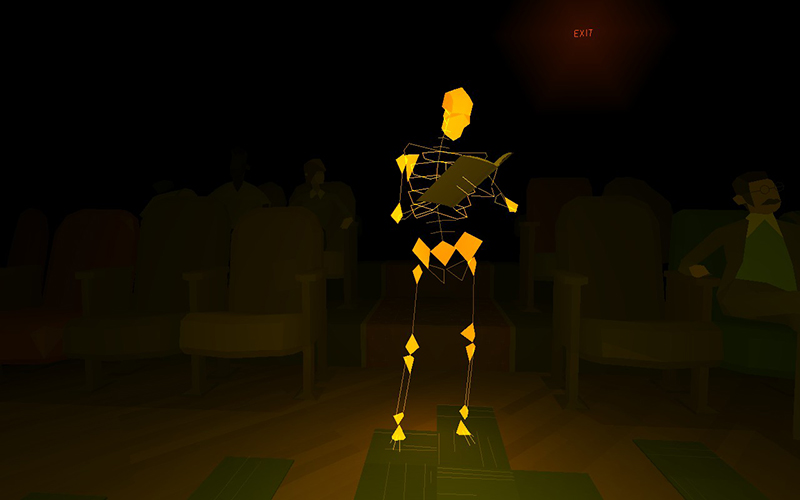

The world of KRZ exists in multiple realities, and the blurry boundary between medias grows as one delves deeper into its universe. While the phone line in the "intermission episode" Here And There Along The Echo (a small, free, bonus game) exists within the virtual world of the game—players interact with the phone (or a representation of a phone) digitally, using a computer—it is also a real phone number that anyone can call. Additionally, a few of the various in-game phone models exist in real life—playfully auctioned off by the developers under pseudonym—and are only able to dial that one, specific number. The fictional art retrospective Limits & Demonstrations likewise exists in-game, but also briefly existed in the physical world as well, with a recreation of the in-game gallery constructed by the Philadelphia-based artist collective, gallery, and exhibition space Little Berlin. Viewers can watch the play The Entertainment on a computer screen (or VR headset), or choose to purchase a copy of the script to read the text on paper; perhaps one day The Entertainment will be recreated and performed in a physical theatre. (Edit: it seems it already has.)

From the choice of preferred media to the bearing you wander to the characters you talk to, there is a choice as to how you experience the story of Kentucky Route Zero. Meaning, even if not readily apparent to players, is intertwined with all conscious or unconscious choices one makes.

Apart from deciding where to physically travel—where to walk, or drive, or fly—the primary form of choice in Kentucky Route Zero comes through choosing characters' dialogue. While dialogue choices in KRZ don't affect the story's narrative or how the plot progresses (apart from its speed), they do allow players to choose emotional personas and dispositions, form backstories, and shape character. Jake Elliott has talked about how, to him, it’s important "not what the player chooses, but that they see the choices, all the ways of being the character the player guides." To me, this is what's essential while playing the game. Describing movement as "guiding" rather than "controlling" seems in-line as well; players do not control a single character in KRZ, but rather drift between the footsteps and dialogue of many. This makes sense, as if one is to truly experience a story from multiple vantage points, one must do so through different eyes and perspectives.

"For us, this idea of parallax—basically that something can be understood more completely when viewed from two different perspectives alternately/simultaneously—resonates with the issue [of] 'relocation.' People are displaced from their homes or places of worship/culture, etc., and then the real tangible and human identity of the place becomes a sort of composite of its former role as a site of life/worship/culture/etc. and its current role as a site of oppression, or as a space that tries to be anonymous but still echoes an oppressive trauma." –Jake Elliott & Tamas Kemenczy

Knowledge of different perspectives, along with cultural and historical knowledge of the environment, is integral to development of the game and the world of KRZ. As a game, KRZ is smart in what it does, in the research and knowledge behind its creation—requirements for its function and existence. The "Kentucky Fried Zero" series of articles by Magnus Hildebrandt brings some of this background to light, exploring various hidden (or not-so-hidden) themes and references throughout KRZ: the many allusions to Eugene O'Neill's The Iceman Cometh, Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Kubla Khan"; the collections of cultural and architectural influences; the homages to early computer programmers, game designers, and story writers. The connections and circularity seem endless. The game pays tribute to these people, this art, and this culture as, without them, KRZ could not be all that it is.

(For more on the characters of Kentucky Route Zero, see my character guide here.)

KRZ encourages players to ask questions and to question their surroundings, both in and out of game. A question asked at the Bureau of Reclaimed Spaces in the second act is, "Is this place inside or outside?" One of the choices, naturally, is "Both." What does it mean to be inside—perhaps between walls or barriers, either physical or conceptual? How can architecture serve to include or exclude? How can we blend dreams and reality, or the past, present, and future, to break or question these dividers? The world of Kentucky Route Zero is imbued with liminality.

In discussing how KRZ encourages engagement and curiosity on the Steam discussion forums, a player states, "It makes you think, but it's not required." Another user responds in agreement—"It doesn't want completion to be the compulsion for learning the story." KRZ rewards exploration, but the drive to explore must be intrinsic. Like most things in life, the game is best experienced when genuinely curious.

The theme of debt is central to Kentucky Route Zero. It's in the soil, the alcohol, the human (or android) histories. It's a unifying theme of the play in The Entertainment. It's a mundane terror, but one that caused the elusive, ghost-like Weaver Márquez to flee. It's rooted in physicality: with Shannon's workshop on the brink of foreclosure, and Conway's leg surgery ("Not my leg.") requiring a sizable repayment.

To whom do we owe things, and what are they worth? Are we responsible for our children, our parents, our family and friends? How do we reach resolution, solace?

JUNEBUG: "We are not saints, but we've kept our appointment. How many people can boast as much?"

JOHNNY: That's lovely, ma'am. Who said it?

JUNEBUG: A poet.

The world of Kentucky Route Zero is haunted—but, rather than in a malignant way, people and places are haunted with memories, with things past. Likewise, there's a sense of repurposing, of adaptation, of change. By name: the Bureau of Reclaimed Spaces, the Museum of Dwellings; by location: the self storage unit turned into a church, the graveyard turned into a chapel turned into a distillery, the caverns turned into a computer workstation paradise. In KRZ, as the world turns and as time passes, debt is perhaps the only stable point of reference.

In the five-act dramatic structure typical of many plays, the fourth and fifth acts reveal the fate of its characters. The two remaining acts of Kentucky Route Zero are approaching—slowly, but with great force. If our story is a tragedy (and it's certainly not a comedy), we'll need this grounded reference—something to hold on to for the future.

Blue

eli

Ryan

eli

Falcon

eli